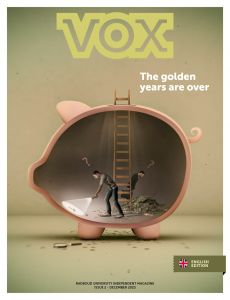

Is there still hope for the corona generation?

Foto: Pixabay/Greymatters (CC0)

Foto: Pixabay/Greymatters (CC0)

It is clear that the economy will enter a recession as a result of the coronavirus crisis. But what does this mean for the graduates now entering the job market? Will there still be work for them? ‘Crises are temporary phenomena and people are inventive enough to adjust to new circumstances.’

For Laura Martens (25), the coronavirus crisis could not have come at a worse time. She was in the process of completing her Master’s programme in Literary Studies, when she landed a contract at an Amsterdam publishing company – her dream job. She was supposed to start in late March. ‘It’s very difficult to find work in my field,’ she says. ‘So I was over the moon.’

Her joy melted away like snow in the sun when the coronavirus started to spread through the Netherlands. Her future employer ran her contract through the paper shredder before she had a chance to start. The reason: the uncertain impact of the crisis on the publishing market. ‘There went my promised income,’ says a disillusioned Martens, who had already relocated from Nijmegen to Amsterdam.

‘It’s an incredible disappointment,’ she says. ‘I find it really difficult to bring some structure to my day and not worry too much. Luckily I still have my thesis to complete, so I’m focusing on that now. And since I’m still a student, I can borrow money for the next five months.’ She doesn’t know what will happen next. ‘I don’t have a plan B.’

Fly home in a hurry

There’s never a good time for a crisis, as Yannick van Duuren can concur. After completing his Bachelor’s programme in Political Science in Nijmegen last year, he moved to India for an internship in IT. ‘Then I saw a vacancy for an internship at the Dutch Consulate in Bangalore. I thought it would be fun to work in diplomacy.’ He applied and got the job. All he needed was for a Certificate of Good Conduct to be sent from the Netherlands.

Van Duuren decided to spend some time in between jobs in neighbouring Nepal. His visa had expired and he had to leave India anyway to apply for a new residence document. From the Himalayas he watched as measures grew increasingly stringent across Asia, but also in Europe. India shut down its borders and tourists flew home in a hurry.

‘I saw the internship at the consulate as an important step in my career’

‘Kathmandu became a ghost town. It got to be too much for me, and I booked a flight back to the Netherlands. All I could find was a business class ticket for the last plane leaving for Istanbul. From Turkey I was able to travel on to the Netherlands.’

And as a result of all this Van Duuren is not socialising with diplomats in the megacity of Bangalore, but can be found at his parents’ house in West Betuwe enjoying a daily traditional Dutch supper. ‘Of course I’m disappointed. I saw the internship at the Consulate as an important step in my career.’ But he can also put it into perspective: ‘I do get free food here, and I can work at my father’s car company on a temporary basis. So I don’t have to worry about money.’

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), economies across the world are being hit hard by the coronavirus crisis. The UN organisation expects a worldwide economic contraction of 3%. The Dutch economy will be hit even harder, with an expected contraction of 7.5%. The consequences for employment are already becoming apparent. Job site Jobdigger, for example, advertised 20% fewer jobs in March than two months earlier.

Uncertain position

This doesn’t bode well for the young, who are always the first to suffer in times of crisis, explains Professor of Sociology and job market expert Maarten Wolbers. ‘In times of economic recession, employers respond by firing staff on flexible or temporary contracts. Unfortunately, young people are overrepresented in these groups.’ They land in a job market that makes it hard to find another job.

All this gets in the way of building what economists refer to as ‘human capital’. Young people in particular acquire skills in the workplace that they didn’t learn in the lecture hall. A long period of unemployment can therefore affect their development and their attractiveness for potential employers. This raises the question: Are these the first symptoms pointing to a new lost generation?

‘Not at all’, responds Wolbers, who has extensively studied the connection between education and employment. ‘Young people always have more difficulty finding a first job in periods of crisis. But the question is whether this uncertain position permanently affects their later career. And my research shows that this isn’t the case.’

Wolbers primarily studied job market data on the 1980s and 2008 crises. These show that young people who began their career in time of crisis suffered the effects for approximately five to ten years. ‘After that they caught up: they occupied as many top positions as other generations, had equal career opportunities, and earned just as much.’

Voluntary work

What about the human capital aspect that unemployed young people miss out on? The key according to Wolbers lies in the fact that during crises, many young people build human capital in other ways than with a permanent job. ‘They do voluntary work, get an internship, or take on a subsidised job.’ This helps them to get a foot in the door with potential employers for when the job market picks up once again. ‘These job seekers have an advantage on new cohorts of graduates because they’ve already proven their value.’

But it does matter whether you’re looking for work in the cultural sector or in AI. While the former sector is already struggling as the festival season goes up in smoke, demand for programmers and machine learning experts is expected to remain high after the coronavirus crisis. This is why Wolbers distrusts thinking in terms of generations. ‘Generations are much too often portrayed as an ideal type. It magnifies differences between generations, while differences within a generation are much bigger.’

‘Even highly educated people often have to make do with a flexible contract’

The ‘lost generation’ concept should be taken with a large pinch of salt. Look at the 1980s, when there were also few jobs to be had. That generation still delivered professors, lawyers and administrators, and ultimately ended up on its feet.

And yet there is an important difference between the job market then and now. Young people find it more difficult than ever to get a permanent job. ‘Even highly educated people often have to make do with a flexible contract, or freelance work,’ says Agnes Akkerman, Professor of Labour Market Institutions and Labour Relations at Radboud University.

Tipping point

In the Netherlands, the economy leans more heavily on flexible workers than in neighbouring countries, says Akkerman. ‘This has advantages, as a large flexible workforce allows the market to respond to a crisis more quickly. Companies can easily fire their staff and are less likely to go bankrupt.’

This high degree of flexibility could mean that the Dutch economy recovers relatively quickly from the coronavirus crisis. At the same time, this system has attracted a lot of criticism: after all, who’s paying the price for it? Akkerman: ‘We’d reached a tipping point; people were becoming increasingly aware of the importance of fixed jobs and job security.’

The findings presented in January by a committee led by former senior civil servant Hans Borstlap were the writing on the wall. The position of employees, freelancers and flexible workers had grown too far apart, the committee concluded. They recommended a complete reform of the job market to ensure that risks and security – or rather the lack of it – were more evenly distributed.

‘What the Borstlap committee really said,’ says Akkerman, ‘is that the Netherlands has taken flexibility a step too far.’ This has all kinds of consequences for employees because, without financial security, people are less likely to buy a house or start a family. ‘Some groups in our society simply can’t afford it – and these are primarily people in a difficult situation, like starters.’

Akkerman wonders out loud how the coronavirus crisis will affect the way people think about flexible and permanent jobs. ‘I can imagine two contradictory scenarios. One is that the trend towards more stability grows. You see a debate arising in society on whether we should try to save all those big companies that refuse to give people permanent contracts. Tax payers are the ones funding all the emergency funds that many companies are now applying for.’

The second possibility is that the coronavirus crisis on the contrary makes people more willing to embrace flexibility within the economy. ‘Because this flexibility could help the Netherlands recover more quickly. And that would take young people who are now in an uncertain position back full circle.’

Back to India

Whatever the consequences of the coronavirus crisis for the job market, Wolbers and Akkerman are both optimistic about the future of those who graduate now. Wolbers: ‘Crises are temporary and people are inventive enough to adjust to new circumstances.’ He believes that the long-term prospects are positive. ‘Our ageing population means that we still have more old people retiring than young people who can take their place.’

Akkerman: ‘Economy is also psychology. If we go around announcing that we’ve entered a long period of recession, then that’s exactly what will happen. You can already see this in the failing consumer confidence. It doesn’t help anyone.’

‘I’m now mostly busy with how to get through the coming period’

Laura Martens, who missed out on her publishing job, can’t say how she will look back on this period five years from now. ‘I’m now mostly busy with how to get through the coming period. In the long run, I’m hopeful that things will work out. Since moving to Amsterdam, I’ve built a small network among publishing companies. People are trying to help, which is nice.’

Yannick van Duuren is even more optimistic. ‘I have a positive attitude to life. The Consulate people have let me know that I’ll be first in line as soon as internships are possible once more. I definitely plan to go back to India. For one thing, my suitcase is still there – I left it behind when I went to Nepal to travel and get a new visa. I might as well pick it up while I’m there.’