What to do with € 90 million

Is Radboud University rich? Yes. But most of its cash is ‘locked’ in buildings. Nevertheless, the Executive Board plans to spend more. Being in the red isn’t something we should fear, but a goal in itself. ‘We try to spend more money than we get.’

Anyone who hasn’t been on Campus for the past ten years or so would hardly recognise Radboud University. Over the past decade, the University has acquired the Berchmanium Academy Building, built the Grotius building, and renovated the Dentistry building and the Elinor Ostrom building. The Refter may still bear its former name, but it’s undergone a massive transformation. And then there’s the colossal building rising from the ruins of the once-so-quaint Thomas van Aquinostraat. Ten years from now, the Campus will probably look very different again, especially now the Erasmus building is due for renovation. And what’s going to happen to the old administration building? And the Spinoza building?

The list of completed and planned building plans on Nijmegen Campus is taking on impressive proportions. And what’s amazing is that Radboud University is paying for all of it out of its own pocket. It’s hardly had to borrow a euro. But how can the University afford it?

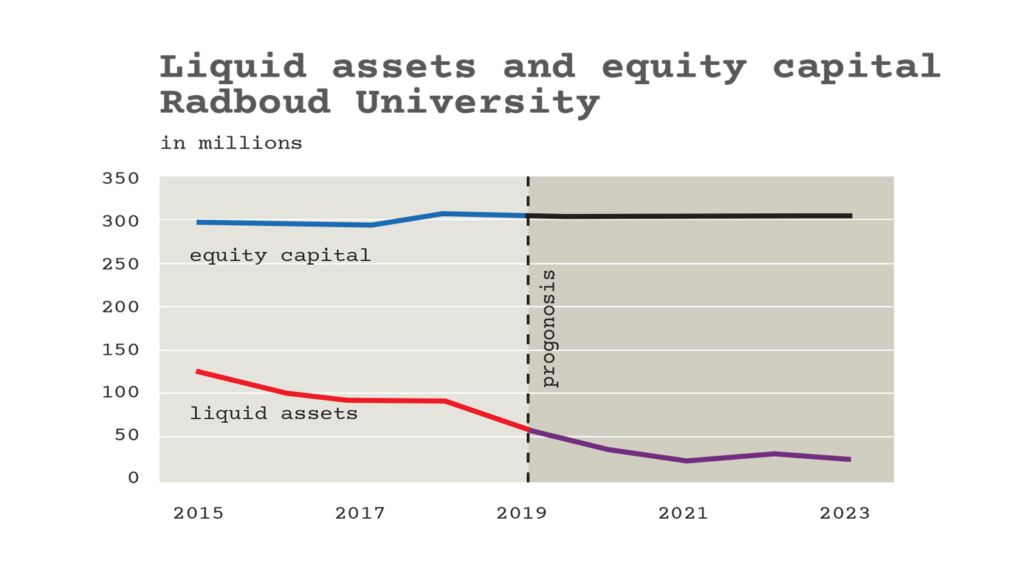

Radboud University’s equity capital is € 306 million (2018). But is the University free to spend this cash any way it wants? Well, not quite. The bulk of this capital is locked in bricks and mortar, consisting as it does of the University’s buildings. You can’t turn buildings into cash overnight. What’s more: where would the lectures take place?

VTo understand why the University has so much capital to its name, you’ve got to go back to the 1990s. At the time, the Dutch government still owned all the university buildings, but wanted to get rid of them, under the pretext of decentralisation. All real estate ended up in the hands of the universities themselves. From that moment onward, the universities owned their buildings, but also had responsibility for them. Buildings require maintenance, and any new buildings would also have to be paid for out of the universities’ pocket. Radboud University was therefore very cautious with how it spent its money in the years that followed, which resulted in positive annual results and a growing capital.

‘Permanent appointments have to become standard again’

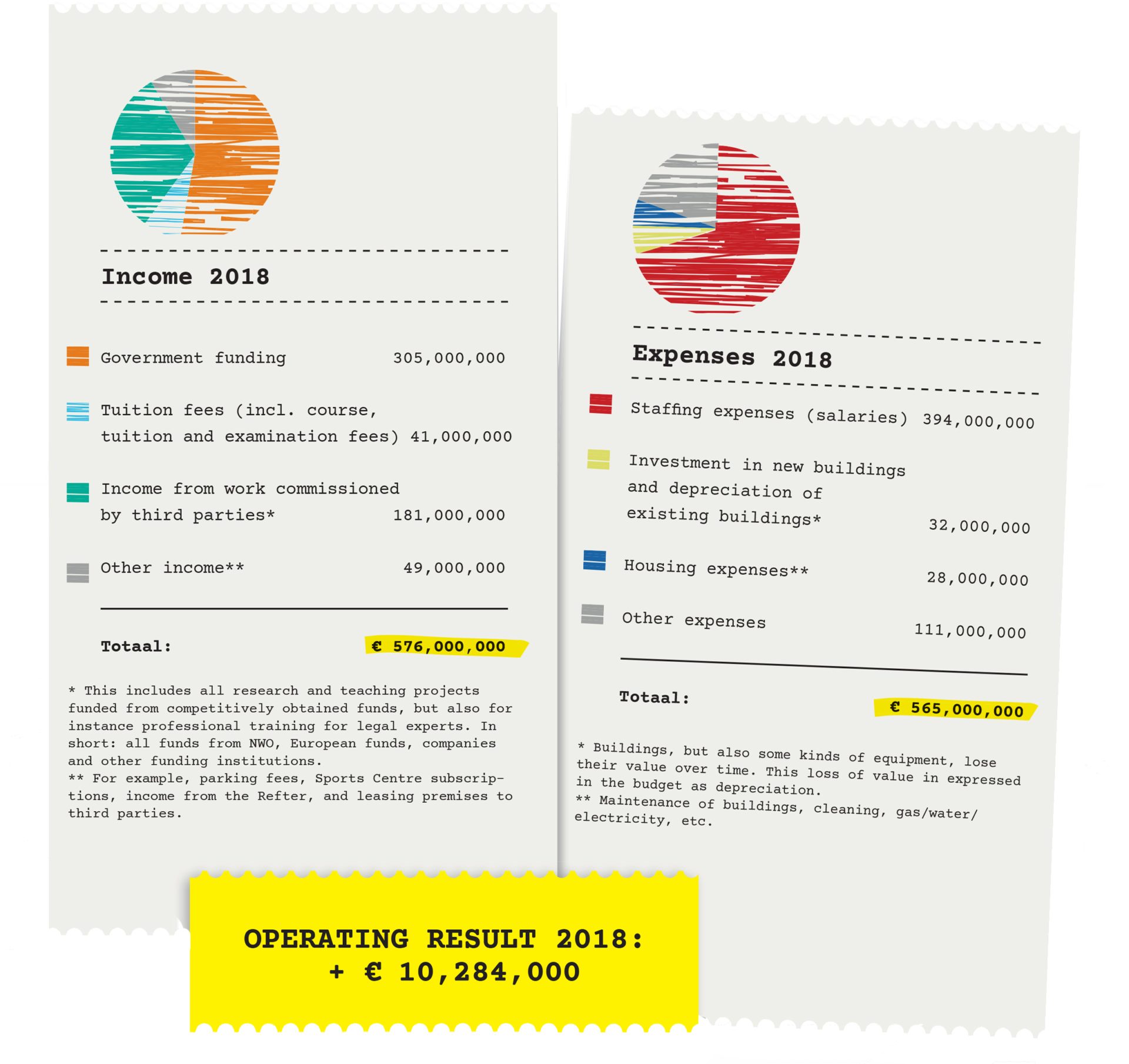

Back to 2019. Most of Radboud University’s fortune of € 300 million is not available for spending. To find out how much Radboud University actually has at its disposal, you have to search the annual report for liquid assets. This is the cash the University has. At the end of 2018, it amounted to € 91 million. Still a substantial amount.

What does the University plan to do with this money?

Radboud University plans to invest no less than € 144 million in real estate in the coming years (until 2023). This money will largely be spent on the Maria Montessori building (approximately € 75 million), but the Erasmus building is also due for renovation in the near future. Other projects include: renovating the Preclinical Institute, home to the Medical Faculty, and the ‘centre plan’, intended to improve the surroundings of the Erasmus building. According to the University’s calculations, by 2023 liquid assets should have dropped to € 20 million. These € 20 million correspond to the lower limit set by the supervisory Foundation Board as the amount required by the University to pay all salaries and bills on time.

But wait a minute. Researchers are complaining about work pressure and uncertainty. Why is nothing being done about that?

The Executive Board has tens of millions of euros, while many researchers continue to suffer from excessive work pressure and have to fight for a permanent contract. This is certainly part of the reality of the situation, admits Wilma de Koning. But according to the Executive Board’s Vice President, the University’s doing everything in its power to solve the problems, financial and otherwise, faced by employees. For example, by offering them permanent contracts sooner. ‘What we need is a shift in culture,’ says de Koning. ‘Permanent appointments have to become standard again. There are no financial reasons at the moment for not offering a permanent contract to an employee who functions well and meets the criteria. This is the message we want to convey as a Board and it’s at the heart of our tenure track and VIDI grant policy.’

De Koning does make a qualifying remark: most researchers working at Radboud University do so on a project base, with funding from research grants and contract research (time-limited grants, for instance from NWO or companies). De Koning: ‘Temporary funds like this account for 40% of our budget. We can’t offer all these people a contract: if we did that, we would create a huge problem for my successor because these funds aren’t guaranteed in the long run.’

‘We know that if there are shortages somewhere, we can make up for them’

A culture of parsimony became prevalent over the last decades. ‘When we started owning our buildings in the 1990s, the government told us to be careful with our money. Saving money was the norm. After all, we were now responsible for the maintenance, renovation and construction of our buildings. And we performed this task exceedingly well.’

De Koning finds it ‘very strange’ that universities are now criticised for this in The Hague. D66 Chairman Rob Jetten recently compared university boards to Scrooge McDuck and called them the ‘proud owners of hundreds of millions of euros in cash, paid for by taxpayers, and which aren’t used for the benefit of students or lecturers’.

Is Radboud University not looking to spend any extra money at all?

They are. Accusations from The Hague that universities are leaving millions unused didn’t fall on deaf ears. ‘We’re doing our best to show a negative operating result by spending money on education, research and buildings,’ says Managing Director Finance Peter Bosman. This may sound strange, but despite a budget with room for additional expenses, the University still made a profit in 2018. And Bosman expects the same to be true in 2019. ‘We can afford a negative result now. But it’s not so easy to achieve.’

For example, in the summer of 2018, the Ministry unexpectedly awarded Radboud University an additional € 5 million for increases in student numbers. Bosman: ‘Three of these five millions went directly to the faculties. They’ve got to come up with their own ideas on how to spend this money. The other two million are reserved for interfaculty collaboration projects.’

This doesn’t mean all this money gets spent just like that. You first have to find employees, write project plans and design buildings – all things that take time. Wilma de Koning: ‘We tell faculties: make sure you put out vacancies for 2020 now, or you’ll be too late. We’re facing a difficult labour market at the moment: good staff are hard to come by. This is one of the drivers behind our new Radboud campaign: ‘You have a part to play!’.’

This doesn’t mean all this money gets spent just like that. You first have to find employees, write project plans and design buildings – all things that take time. Wilma de Koning: ‘We tell faculties: make sure you put out vacancies for 2020 now, or you’ll be too late. We’re facing a difficult labour market at the moment: good staff are hard to come by. This is one of the drivers behind our new Radboud campaign: ‘You have a part to play!’.’

What is the role of the faculties?

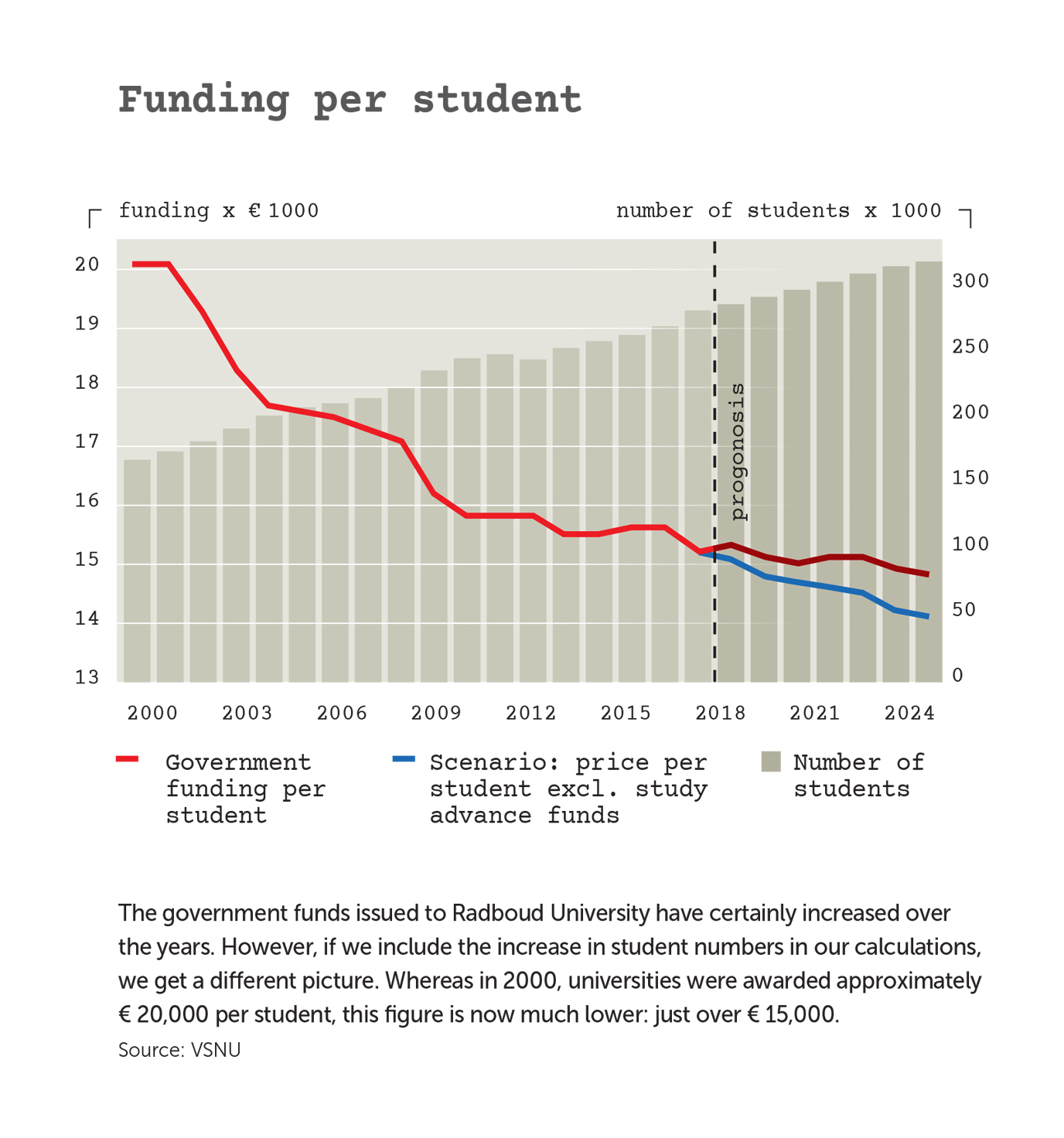

The bulk of the universities’ income comes from the Dutch government; this is known as direct government funding. And just as the government in The Hague distributes its funds for higher education among research universities and universities of applied research, similarly Radboud University in turn distributes these funds among its faculties. This is done as fairly as possible: ‘We use many of the same distribution principles as the Ministry,’ says Managing Director Finance Peter Bosman. ‘For example, we also look at student numbers and successful PhD tracks. Every faculty gets a fixed amount per student, degree awarded and PhD defence.’

And yet, the internal distribution model does differ somewhat from that of the Ministry. ‘Our internal model uses larger fixed bases, i.e. amounts that remain constant. The proportion of funds that depends on flexible variables – for example student numbers – is smaller: it accounts for approximately 40% of the distribution model.’ So if the Law Faculty doubles its student numbers, it won’t suddenly get twice as much money. Conversely: if enrollments lag behind, the Faculty won’t immediately run into financial problems. Bosman: ‘We have to ensure calm and stability.’

Finally, the faculties are relatively financially independent. They’re free to decide how to distribute their money internally (within the legal frameworks). Every faculty has its own rules, although its budget must be submitted to the participational bodies and the final balance approved by the Executive Board.

What about cost cuts from The Hague?

In May, the Van Rijn Committee presented a report recommending shifting tens of millions of euros from the social and medical sciences and the humanities towards science and technology. The reason: the Netherlands needs more qualified science and technology experts to retain its economic edge. The report caused quite a stir, especially at broad universities like Radboud University. The implications are that Nijmegen will receive € 4 million less from the Dutch government in 2022, and € 3 million a year less in the following years.

During Prinsjesdag, in addition to the cost cuts mentioned here, it was also announced that the interest increase on student loans would be abolished (the Minister had withdrawn this plan in June under pressure from the House of Representatives). In the long run, this represents cuts worth millions of euros. Not to mention the reintroduction of the basic grant, which is fast gaining majority support in the House of Representatives. Does this mean an end to the additional education funds the universities were due to receive from The Hague as a result of the introduction of the student loan system?

In response to fluctuating national policy, the Executive Board of Radboud University calls for everyone to remain calm. For the next two years, the Board has already agreed not to shift any additional funds towards science at the expense of other faculties. But in the long run too, the general message is that faculties should continue to make plans. ‘Our strategy now is to distribute funds more generously among the faculties,’ says Wilma de Koning. ‘We know that if there are shortages somewhere, we can make up for them. This is also true for reduced funding as a result of the Van Rijn report. Which is not to say we can afford to throw money away.’

The new Vox, which is about money, can now be read online. Next week the English magazines will be spread around campus.