Researcher Samira Azabar finds Radboud University pretty white

-

Foto: Bert Beelen

Foto: Bert Beelen

Samira Azabar (38) is known in Belgium as the figurehead of BOEH! (Baas Over Eigen Hoofd, Boss Of Your Own Head, an action group defending the right to wear a headscarf). This year, she started out in Nijmegen as a postdoctoral researcher. ‘People wondered: “Are you capable of doing a PhD?” Based on the idea that a woman wearing a headscarf can’t possibly be objective.’

When Samira Azabar started her PhD research in 2018, she discovered something about herself. She studies political participation and perceptions of gender and sexuality among Muslims, first in her PhD at the University of Antwerp, and since March, as a postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Social Sciences in Nijmegen. In her doctoral research, she analyses people’s behaviour both inside and outside the voting booth. What kind of action groups do Muslims set up? How do they express themselves on social media? And how do they deal with discrimination? The latter in particular touches her personally, says Azabar. ‘When I heard people in my interviews explain the strategies they use against discrimination and marginalisation, I thought: I sometimes do this too, and that’s something I do very consciously.’

‘I came here and thought: Oh, wow. Radboud University is pretty white’

Azabar sits at a table on the terrace of a restaurant in Brakkenstein, sipping her iced tea. Her wheeled suitcase is standing next to her: she’s attending a conference at the University tomorrow, and has to be there early. ‘Popping up and down’ to her hometown of Antwerp is out of the question, so she’s spending the night in a hotel. Azabar is wearing her go-to jumpsuit, with its bright, eye-catching geometric shapes. Her headscarf is tied at the back of her neck.

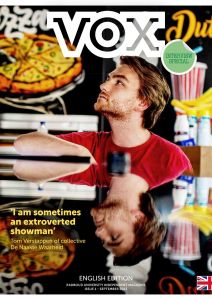

This interview is part of Vox’s interview special, which can be found in the Vox stands on campus, starting next week. The magazine contains interviews with student and NEC player Dirk Proper; virologist Marc van Ranst; producer Tom Verstappen; doctor Tanya Bisseling and her student daughter Jasmijn Olde; friar Stefan Ansinger; and influencer Manon van den Bos.

‘I deliberately wear a cheerful outfit like this,’ she says. She also deliberately wears her headscarf knotted at the back of her neck at work. Azabar finds that this makes it easier to connect with people who are not used to a headscarf. When she first applied for a PhD position in Antwerp, an academic colleague explicitly told her: I find you more accessible that way. These are strategies that Azabar also hears from her respondents.

Azabar may not yet be a well-known face at Radboud University, but she is in Flanders. She is one of the figureheads of Baas Over Eigen Hoofd (Boss Of Your Own Head, BOEH!), a feminist and anti-racist action group that defends the right to wear a headscarf. Her social commitment did not end when she began her career as a researcher. In fact, the two go rather well together, Azabar believes.

How do you like it at Radboud University?

‘I’m having a great time, and I have amazing colleagues. I did expect there to be more differences with Belgium though. In Belgium, the Netherlands has a reputation for considering diversity very important, but I see little difference. In promotional photos, the University tends to present itself as rather atypical, I think.’ She laughs. ‘But then I came here, and I thought: oh, wow! Radboud University – and its surroundings – are actually pretty white.’

At what age did you first feel that others saw you as ‘different’?

‘At a very young age. In primary school, I had to give a presentation on Morocco, even though I was born and raised in Belgium. After the 9/11 attacks in the US, I was often asked why Islam is so violent. I felt awful when teachers or friends asked me such questions. I thought: You’ve known me all this time, where is this suddenly coming from? Before the 9/11 attacks, I was asked other questions: Why are women subordinate to men in your culture? Are you against gays? And all I could think was: That’s not how it is at our house. I started seeking answers at a young age, so I could respond and explain why I’m a Muslim. That’s why I chose to study sociology, I think.’

Azabar grew up in Mechelen in a family with five brothers and four sisters. Her parents are first-generation migrants from Morocco, and they have a different take on discrimination. ‘My parents used to say: it will blow over. While I saw that discrimination was growing.’ Azabar was taught at home that religion is very peaceful. ‘I was brought up with anti-neoliberal ideas: the collective and caring for vulnerable people are important.’ As a child, Azabar read a lot and watched lots of documentaries. Her parents’ attention was more often focused on some of her siblings. ‘Now that I’ve got children of my own, I kind of understand it. I was always doing fine anyway.’ At the end of primary school, and despite her good grades, her teachers were unwilling to send her to pre-university education. So her older sister intervened. ‘She came along to the parent-teacher meeting as an interpreter, and tried to convince my parents.’

At age 10, Azabar decided to start wearing a headscarf. ‘Looking back, I think I was quite young. My parents said: it will make things harder for you. But it gave me comfort, and recognition. I wore it when praying, and it felt really weird to keep putting it on and taking it off. So I thought: I’ll just wear it all the time.’

At your Catholic secondary school, you had to take off your headscarf. How did that feel?

‘As if I suddenly didn’t belong anymore. In primary school, my classmates would sometimes pull it off, but now it had to go altogether. Things became especially difficult later, when religion started to play an even bigger role in my life. When I was 17, my brother died of a brain haemorrhage at the age of 23. That same year, the 9/11 attacks happened. I was much more focused on my prayers and ritual practices after that. That kind of thing happens automatically when you’re in a grieving process.’

You mention the two events together, as if they were of the same order of magnitude.

‘Yes.’ She is silent for a moment. ‘Yes.’

And are they?

I don’t know. The two experiences had a different, but significant impact. And both influenced me a lot. I personally suffered more from my brother’s death. The 9/11 attacks impacted how people saw me. I was no longer the exotic Moroccan with the lovely mint tea, but a potential threat.’

After completing secondary school, Azabar went on to study sociology. She then worked as an educator at Motief, an educational institution focused on philosophy of life and society. In the meantime, a fierce social debate about the headscarf was raging in Flanders. In 2007, the Antwerp city council forbade the wearing of headscarves at the municipal desk. This led to street protests. In response, a number of women of all backgrounds and faiths – including Ida Dequeecker, a Flemish feminist of the first hour – founded Baas Over Eigen Hoofd (Boss of Your Own Head). A year later, Azabar became involved with BOEH! through her work. And some 15 years later, she is still involved. Last year, Azabar and Dequeecker published a book about the organisation.

BOEH! explicitly calls itself a feminist organisation. Is wearing or not wearing a headscarf the same kind of choice as wearing a short skirt?

‘Of course. We’re also very deliberately called Baas Over Eigen Hoofd, in reference to Baas in Eigen Buik (Boss Of Your Own Belly). Feminism is all about the freedom to make decisions. We stand for radical self-determination for women, a right they still don’t have to this day. The prevailing view these days is that Muslim women are oppressed, and if we were only to free them, all problems would be solved. But that isn’t how it works. The evil is patriarchy and racism, not Muslims. In places where decisions are made, it is still mostly white highly educated men who decide how everyone else should live. At BOEH!, we thought that if we simply explained that we weren’t oppressed, everything would be fine.’

Three questions for Samira

What did you want to become when you were little?

‘Doctor.’

Where did you go this summer?

‘Alanya in Turkey (all inclusive) where you can simply enjoy a rest and not have to do anything for a while. When you have young children, that’s absolute bliss.’

Who do you admire?

‘I especially admire people who stand up against injustice and dare to dream of a just and more equal society.’

But that wasn’t what happened. You quickly became the face of BOEH! and received a lot of negative media attention.

‘They said: you’re good at explaining it, so you do it. None of us had had any media training. So I did it, but I didn’t enjoy it at all. I was very stressed and I had to voice an opinion that was unpopular. I also found it frightening to go into a TV studio. I was in my early twenties, remember!’

In 2009, in an interview on national television, well-known Flemish philosopher Etienne Vermeersch called you a fundamentalist Muslim because of your headscarf. How do you look back on that now?

‘It was rough. We didn’t want to just preach to the converted, which was why we wanted to enter into dialogue with people like Vermeersch or the leader of Vlaams Belang. The image of a young Muslim woman facing an older white man who wanted to dictate how women should dress helped us connect with other feminist organisations that were initially against us. BOEH! was taken seriously after that, in part thanks to those media appearances.’

Do you see similarities with the current situation in the Netherlands, where headscarves were recently banned in the police force?

‘In Belgium, the discussion arose after France banned headscarves in the 1980s. The Netherlands is in turn taking over that discourse from Belgium. You can see clearly that people keep referring to a false interpretation of neutrality.’

You mean the idea that someone can’t be neutral AND wear a headscarf. But do you think they can?

‘Yes. And funnily enough, so does the Flemish government. On their site, it says that neutral service is not about what you wear, but about whether you can assist citizens without bias. That’s the definition of neutrality.’

In the Netherlands, the ban covers all religious expressions, according to the responsible minister, Dilan Yeşilgöz.

‘But the social debate always focuses on Muslims. The debate on face coverings on public transport was also only about burkas. When this kind of thing then becomes law, it should be defined in neutral terms. Antwerp’s ban on headscarves also included skull caps and piercings, but people still continue to wear them.’

Did you find it hard to transition from being an educator and activist to academia?

‘No. Other people wondered: “Are you capable of doing a PhD?” Based on the idea that a woman wearing a headscarf can’t possibly be objective.’

‘The idea that I am biased because of who I am is simply mistaken’

Was this also due to your activism?

‘My academic colleagues would say to me: activism isn’t quite the same as scientific research, you know. But their objections were mostly about my appearance. Someone told me once that I would be limited in the scope of my research. In my PhD dissertation, I was asked to write a chapter on my positioning. I was very much against this initially. Other people didn’t have to do it. The idea that I’m biased because of who I am, while white researchers are neutral and objective, is simply mistaken.’

Your life and your research are hugely interconnected. Isn’t that relevant?

‘That’s often the case. In fact, I think every researcher should write such a chapter. Some of my colleagues are members of political parties while doing research on political parties. I think that poses even more of an integrity issue than me and my headscarf.’

Have your activism and background also benefited you?

‘Yes. Two of the four Muslims I’ve interviewed so far in the Netherlands sought me out and agreed to the interview because of it. They wanted to know who I was, and what I stood for. And in my role as activist, I’ve learned a great deal about politics and society.’

You are still committed to BOEH!, doing your research, commuting six hours a day back and forth to the University. In an interview with Flemish magazine Ferm, you said you were ‘plundering’ your body. So why do you do it?

‘I do it because it’s necessary. My children are still seen at school as ‘different’, or underestimated because of their background. It makes me think: it’s been two decades since I went to primary school and nothing has changed. This is also why I’m on the parents’ council at their school. For a long time, I just kept on smiling and conforming, as my parents had taught me. But I’ve found that you achieve very little that way.’