GI Doctor Tanya Bisseling researches the hereditary form of cancer that runs in her family

-

Jasmijn Olde (links) en haar moeder, arts Tanya Bisseling voor het Radboudumc. Foto: Erik van 't Hullenaar

Jasmijn Olde (links) en haar moeder, arts Tanya Bisseling voor het Radboudumc. Foto: Erik van 't Hullenaar

Twenty-one years ago, physician Tanya Bisseling identified the first Dutch patient with a rare form of stomach cancer. The patient was herself, and she was pregnant at the time. To save her life, her stomach was removed. Recently, the same surgery was also performed on her daughter, a medical student at Radboud University.

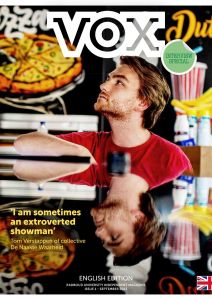

This interview is part of Vox’s interview special, which can be found in the Vox stands on campus, starting next week. The magazine contains interviews with student and NEC player Dirk Proper; researcher Samira Azabar; virologist Marc van Ranst; producer Tom Verstappen; doctor Tanya Bisseling and her student daughter Jasmijn Olde; friar Stefan Ansinger; and influencer Manon van den Bos.

Tanya Bisseling is sitting at her kitchen table in Nijmegen, a mug of coffee, and several black-and-white photographs spread out in front of her. It’s Wednesday morning, just after eleven, and Bisseling’s dogs start barking. ‘Sorry, they react to everyone who goes past the garden,’ she says.

It’s unusual to find Bisseling not working on a Wednesday like this. Normally, the gastroenterologist would be doing paperwork, responding to patients, and giving lectures at the university. ‘I should probably take better care of myself,’ she says. ‘I really do work a lot.’

Bisseling is a world-leading expert in a rare hereditary form of stomach and breast cancer caused by a mutation of the CDH1 gene. It’s a mutation most people have never heard of. Bisseling suspects that no more than 30 or 35 families are affected in the Netherlands. Twenty-one years ago, she identified the first Dutch patient: a medical student in her early thirties, twelve weeks pregnant, with an early form of aggressive stomach cancer. Herself.

Gastrectomy

Twenty-one years ago, a pregnant Bisseling underwent a gastrectomy, removal of the stomach, that stopped her cancer from spreading and saved her life. Her youngest daughter, Jasmijn Olde, who she was pregnant with at the time, had the same surgery less than a week ago. Her daughter is the reason Bisseling is at home right now, on care leave from work.

When we spoke for the first time, Olde was just a few weeks away from surgery. The twenty-year-old medical student had been diagnosed with the same aggressive stomach cancer as her mother two decades previously, in late 2022. For Olde, the diagnosis did not come as a surprise. She has known for four years now that she is a carrier of the genetic mutation.

‘Usually, you don’t test before someone turns eighteen,’ her mother explained when we met before the surgery. ‘But she was very mature for her age, and the three of them, my oldest daughter, my son, and Jasmijn, wanted to be tested together.’ Both Olde and her brother turned out to be carriers. Last year, her brother had his stomach removed.

Priorities

Jasmijn Olde, a medical student at Radboud University, now joins her mother at the kitchen table. She was released from hospital a few days ago and is slowly adapting to life without a stomach.

‘I’m really looking forward to eating normal food again, especially friet speciaal‘

‘The pain is getting less,’ she says. ‘But I have a lot to think about now.’ Losing a stomach shifts priorities, she says. Right now, Olde’s priorities are getting enough food and sleep. Neither of which is exactly easy without a stomach. The first two weeks after the surgery, she can only consume fluids, has to eat every two hours, and every bite takes time. Her friends have been visiting and she is managing to have a walk around the block: ‘Maybe 500 meters a day,’ she says. But everything is tiring. And every bite is complicated.

‘If food doesn’t enter the stomach the right way, air comes up, fighting with the food coming down, and making her nauseous,’ her mother explains. And the fact that Olde’s diet mainly consists of soup and yoghurt at the moment doesn’t make it any easier. ‘I’m really looking forward to eating normal food again,’ she says. ‘Especially friet speciaal.’

Relief

But eating will never entirely return to normal. For a start, when a stomach is removed, a person loses their feeling of hunger, because the proteins that send hunger signals to the brain are produced in the stomach. ‘Sometimes, I feel a little bit shaky, but that’s the only sign your body gives,’ says Olde. For her, food will now be something she needs to remind herself about, something with a schedule attached.

‘Having your stomach removed is like starting from zero,’ she says. ‘You lose all your health, all your fitness. A social worker I talked to before the surgery said it can almost feel like a mourning process for your old life.’ Before the surgery, she mostly felt one thing: ‘Really scared.’

Three questions for Jasmijn

What did you want to become when you were little?

‘I always said I wouldn’t be a doctor. But, here I am, studying Medicine.’

Where did you go this summer?

‘Mallorca, a holiday full of sun and beach.’

Who do you admire?

‘I find it hard to name one person I admire, I’ve thought about it for a long time… but I just admire lots of people. Everyone around me, my friends, acquaintances and family, they all have some characteristic that I admire.’

Now that the surgery is over, this feeling has turned overwhelmingly into relief. ‘I woke up after the surgery and just started crying. I didn’t even think about it. It just happened.’ Olde is not a person who cries easily: ‘I was a bit surprised myself,’ she says.

Her mother was less surprised: ‘I think there was tension inside of you on the run-up to the surgery,’ she adds. ‘You didn’t allow it to come out. And after the surgery, it exploded out of you.’

Appreciation

In the weeks leading up to the surgery, Olde decided to make the most of her final days without a handicap. Going to university, to the pub, working, being out all the time. ‘Until five in the morning,’ Bisseling says. ‘But I stopped a few days before the surgery,’ her daughter replies. ‘Then I felt like I should probably get some rest. It’s not a good idea to go into surgery tired.’ But knowing that she would lose her health, she says, has definitely made her appreciate it more.

‘She will find her way; it will be alright’

Now, the twenty-year-old will spend the upcoming weeks slowly learning to eat again and trying to come to terms with this new version of her life. According to Bisseling, patients’ bodies take around two years to really adapt to the loss of a stomach.

‘I think I will have to prioritise studying above student life this next study year,’ Olde says about going back to university. It will probably be tough, she thinks, but she is motivated. ‘I signed up for the Honours programme, I really wanted to do it, and this was my only chance.’

But right now, the tiredness is affecting her a lot. It was one of the things she thought would be most challenging before the surgery: ‘Everyone around me will be twenty years old and partying, and I will be in bed,’ she predicted back then. At the moment, she spends most of her time on the sofa. ‘I’ve been watching a lot of television, especially sports programmes, which I never used to watch before.’ She laughs: ‘I know a lot of tennis players now.’

Death sentence

‘She’s not ready to hear that yet,’ Bisseling says after Olde has gone to lay down again. ‘But she will find a way; it will be alright. What I tell my patients is that stomach removal is like a lifelong punishment. You will always have to worry about what to eat, always have to prioritise, and you can’t predict when you will have a good day – and when a less good one.’

In the future, Bisseling hopes that more stomachs can be retained until patients are in their thirties or forties. ‘In some people, we remove a stomach for small indolent (early, ed.) lesions. These are malignant, but some of those tiny, early malignant lesions will never develop into invasive cancer. So, we try to identify a changing pattern and individualise the moment of gastrectomy.’

Olde’s cells had already started changing into a more aggressive form. ‘Not having surgery would have been her death sentence,’ Bisseling says. In 1997, Bisseling’s father, then 54, died of stomach cancer. ‘He was a heavy smoker; he worked even more than I did,’ she says. ‘So, I thought, well, he smoked too much; his lifestyle caused his cancer.’ Then, only a few years later, her 25-year-old sister was diagnosed with the same type of cancer, already incurable.

Hereditary

‘The carriers are very difficult to identify,’ Bisseling says. ‘You discover the gene in the family because people die.’ Like Bisseling’s father and sister. The fact that she discovered the hereditary stomach cancer her family was affected by in the early 2000s is a miracle. Back then, genetic testing for inheritable cancers was still in its infancy.

‘You discover the gene because people die’

‘I discovered that it was possible to analyse this CDH1 gene, that I thought our family had a mutated variant of and that caused the cancer, in Cambridge in the UK, so I contacted them.’ It took months for the results. By the time Bisseling learned that her suspicions were correct, an endoscopy had already detected cancer in herself and another of her sisters, and both had their stomachs removed.

Bystander

‘The bitterest feeling is thinking about my sister who died of stomach cancer,’ Bisseling says. ‘Because the fact that she had an incurable stomach cancer saved the lives of my other sister and me. And she knew; she was aware of that.’ The black-and-white photographs on the table in front of Bisseling are from the final months of her sister’s life. Some are from the funeral.

‘She never complained,’ Bisseling says, looking at the photos. ‘No. Until the last month, when she wasn’t able to do anything anymore, she celebrated life.’ How does that make her feel? ‘That’s the thing, I can’t say,’ she says. ‘For my younger sister who also had her stomach removed, it was much more difficult. They were only a year apart, almost like twins. I felt like a bystander.’

There were only three months between her sister’s terminal cancer diagnosis and the removal of Bisseling’s stomach. At the time of her surgery, Bisseling and her husband had two young children and a third one on the way. ‘You haven’t got much time to think about it,’ Bisseling’s husband Erik Olde says. ‘You just get on with it. And afterwards, you think, how did I manage that?’

Unchartered

‘I remember Erik being more shocked than I was,’ Bisseling says. ‘I remember myself saying, okay, if there is cancer, we have to remove my stomach. And then my gastroenterologist said, okay, but then we have to carry out an abortion first – that was Jasmijn – and I said, no, we’re not going to do that.’

Three questions for Tanya

What did you want to become when you were little?

‘A doctor; it was the only thing I ever wanted to be.’

Where did you go this summer?

‘Mallorca. Nothing special – just a holiday to chill out and recover.’

Who do you admire?

‘My family (my husband and three children).’

Nowadays, Bisseling says, she has more patients without stomachs having babies. But twenty years ago, this was unchartered territory.

The fact that many aspects of the illness still need more research is one of the reasons why Bisseling has started talking publicly about her own story in the media in the last year. ‘I try not to let the illness interfere with my life. I run half marathons; I do the Four Day Marches. Until a year ago, only my family and friends knew I was ill – and, of course, my colleagues and patients.’ But it does have an impact – on her, her children, and other patients affected, many of them young people.

‘I sometimes think every doctor should have to be a patient for a week’

‘It’s an invisible illness,’ Bisseling says – and that, precisely, is one of its biggest challenges: ‘Even my colleagues don’t understand. People think that I’m healthy and can do anything. I look normal and I behave normally, but I’m not normal. I have a serious illness.’ Seven years ago, Bisseling had to undergo more surgery to have her breasts removed after early-stage breast cancer had been detected, also linked to the mutated CDH1 gene.

Perspective

‘In the beginning, my colleagues thought that it was unprofessional to tell my patients that I’m a carrier too,’ she explains. But Bisseling told them anyway. ‘And patients are glad to hear it. They know I’ve been through everything they have been going through. And the patients, she says, are what she truly cares about in her work. I sometimes think every doctor should have to be a patient for a week. That’s impossible, of course.’

But she thinks that being a patient has given her a different perspective on her work – and she is certain that her daughter will one day also have a different perspective than other physicians, based on her own experiences with the illness.

She talks about the day she met Parry Guilford, the biomedical scientist who first identified the CDH1 gene in the mutated variant that causes the cancer affecting Bisseling’s family. Thanks to Guilford’s publication, Bisseling was tested more than twenty years ago. ‘I introduced myself,’ she recalls that moment in 2014. ‘And I said: it’s thanks to you that I’m alive.’