How much effect does a cup of coffee have? Researchers study reaction time on festival site

-

Coffee. Foto: Chevanon Photography via Pexels

Coffee. Foto: Chevanon Photography via Pexels

Does having a cup of coffee give you energy for the rest of the day, or do you immediately want another? The answer to that question may partly depend on a single piece of your DNA. This year, Radboud researchers are at Lowlands to study how much your DNA influences the duration of the effects of your cup of coffee.

‘It has long been known that there are certain variants in DNA that enable some people to metabolise caffeine faster or more slowly,’ says PhD candidate Noor Verhagen from the Department of Pharmacy, Pharmacology and Toxicology at Radboud university medical center. Verhagen and her colleagues want to test that fact by measuring the reaction time of people at Lowland. The first measurement is taken before people have a coffee and repeated half an hour later.

Caffeine improves reaction time. So in theory, the second test should show that people whose DNA says that they metabolise caffeine slowly do feel more benefit than fast metabolisers. The Pink Coffee Club, as the research team is known, hopes to see exactly that reflected in the results of their DNA and reaction tests.

‘Besides that DNA variant, there are many other issues involved, so we also want to gather information through a survey,’ Verhagen says. After taking a baseline measurement for reaction time, those taking part in the research may have a cup of coffee (with or without caffeine, because there is also a control group). Afterwards, participants answer a detailed questionnaire on a variety of factors that may affect how coffee affects them and their reaction time. A breathalyser test is also conducted. ‘Obviously, coffee isn’t the only beverage consumed at Lowlands,’ Verhagen laughs.

Shipping containers

After that, the subjects actually enter the lab. A shipping container will house a real laboratory where PCR tests will be carried out. These are roughly the same tests used to determine Covid-19, for example, except that the researchers are now looking at a completely different piece of DNA. DNA consists of four types of building blocks – called bases – which are denoted by letters A, G, C or T. The entire human DNA consists of some three billion bases, but the characteristic of whether you metabolise caffeine quickly or slowly is determined by a single base. Verhagen: ‘If you have a C-base in that spot, we label you a slow metaboliser.’

‘We don’t expect people to hang around in our shipping container for several hours’

The PCR test takes DNA – involving a painless buccal swab that captures cells from the inner cheek – and multiplies the relevant piece of the DNA so many times that you can see it with the naked eye as a kind of band. Then a special enzyme – like molecular scissors – cuts open only the DNA that has a C-base at that specific spot. This creates two separate pieces of DNA, i.e. two bands. ‘In the case of fast metabolisers, you only see one band of DNA after the test,’ Verhagen explains. ‘This is because it was not cut due to the absence of a C-base. In the case of slow metabolisers, you do see two bands, because the enzyme has cut the DNA.’

‘The entire investigation takes several hours,’ says Verhagen. ‘But we don’t expect people to hang around in our shipping container for that long,’ she says reassuringly. Test subjects will be emailed their own DNA variant.

Old Dutch game

Half an hour after having the coffee, the reaction test is repeated. That consists of an Old Dutch Catching Sticks game and an electronic version of whack-a-mole. People with the slower variant of the metabolising gene in their DNA are expected to have more caffeine in their blood during that second reaction test and can therefore set a faster score. The research team hopes that this will actually be reflected in the results, even though these depend on many other factors.

Verhagen: ‘We are going to see whether we can link the reaction test score to the DNA variants.’ However, the researchers are also interested to find out whether the participants can assess for themselves whether they are a fast or a slow metaboliser. ‘For example, I’m a fast metaboliser,’ Verhagen says of her DNA test. ‘I also drink a lot of coffee in a day, so that may be true.’

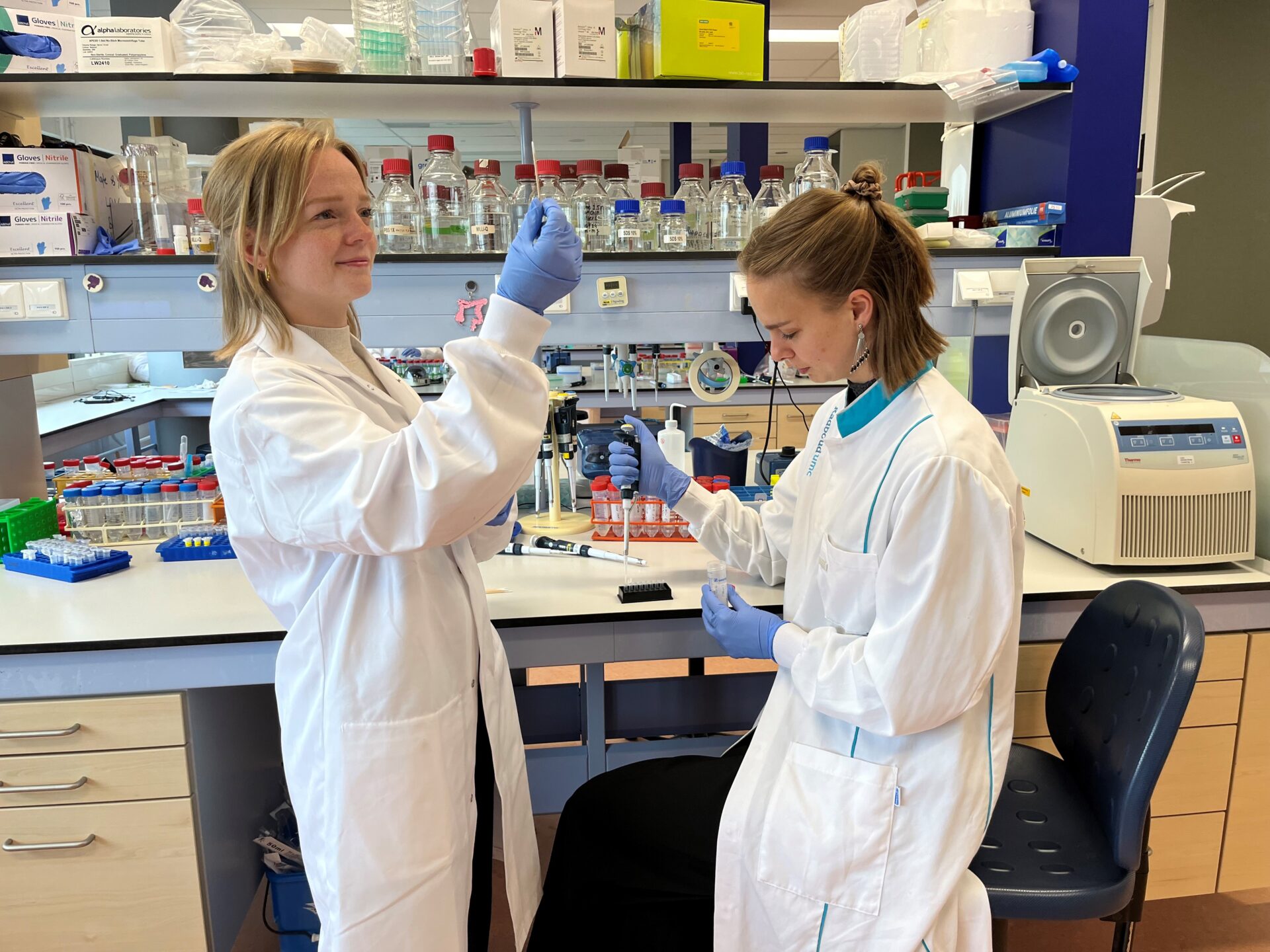

In everyday life, Verhagen and her fellow PhD candidate Margit Janssen from Radboud University’s molecular biology department are involved in molecular cancer research. Going to Lowlands means taking a trip into the world of coffee. However, according to Janssen, that isn’t too much of a diversion: ‘In our research, we also often look at drug metabolism, but it can sometimes be very hard for society as a whole to understand exactly how that works.’

Festival fun

To introduce Lowland festivalgoers to scientific research and build a bridge to processes involved in the development of medication, the researchers are swapping their medicines for coffee. Amid what can be high festival prices, they hope that the ‘free coffee’ sign will appeal.

Besides their own research, for which they expect around five hundred subjects, there will also be time for the pair to enjoy what else Lowlands has to offer. For example, the researchers will also check in with their colleagues from the gynaecology department. They are also on site to conduct research on menstrual problems, including a symptom simulator for men.

After the research has been completed, Verhagen and Janssen will swap their laboratory for the festival site. ‘When we’ve finished, we will definitely check out Chappell Roan.’