Students are no longer looking for a room: more students are living at home than a few years ago

-

Student rooms on Jacob Canisstraat. Photo for illustration. Photo: Bert Beelen

Student rooms on Jacob Canisstraat. Photo for illustration. Photo: Bert Beelen

Fewer and fewer students are moving out of home. They continue to live with their parents and have given up hope of getting a room, the National Student Housing Monitor shows.

Eight years ago, 52 percent of all students lived on their own and another 7 percent were eager to move out, amounting to a total of 59 percent. Now, only 44 percent are living away from home, while only 5 percent are looking for a room. That’s a total of 49 percent.

So, the percentage is much lower than eight years ago. Students are giving up hope of finding suitable housing, is the conclusion of student housing knowledge centre Kences.

Consequences

The housing shortage is affecting the accessibility of education, believes Kences director Jolan de Bie. After all, sometimes the programme of your choice is too far away to continue living at home with your parents. So what do you do if you can’t find a room?

She’s also concerned that students living at home miss some of the social-emotional development ’that is crucial for young people at this stage of life’. These students may feel partly excluded from student life, which in turn may lead to lower self-esteem, De Bie states.

There are several reasons for the shortage. About five thousand student rooms were added last year, but things went awry in the private market. The number of students in private rented housing has decreased by 17,800. Various organisations are sounding the alarm: new government laws and regulations protect tenants from exorbitant rents and make homeowners pay more taxes. As a result, many homeowners are putting their student houses up for sale.

Flexibility

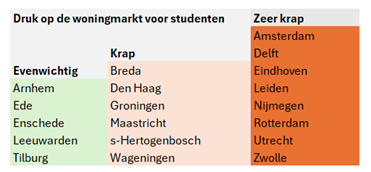

There are about 322,400 student rooms in the nineteen student cities. That’s an estimated 13,500 fewer than in the 2023-2024 academic year. In five of the 19 student cities, the housing shortage amongst students isn’t all that bad. These are Arnhem, Ede, Enschede, Leeuwarden and Tilburg. In the other cities, the pressure is high or even very high, according to the monitor.

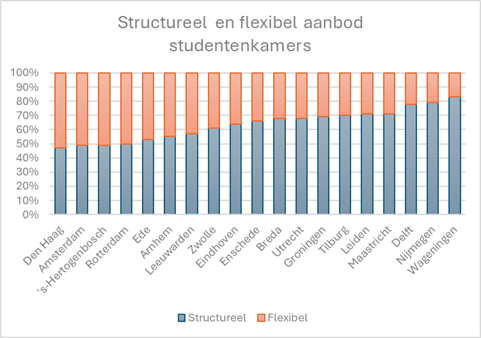

The researchers also looked at where the supply of student housing is ‘structural’. That is, in which cities do students live in rooms that are permanently intended for students, and where do they just happen to live in housing that could go to someone else next time or even disappear? The latter is what the researchers call the ‘flexible’ supply.

In The Hague, Amsterdam and Den Bosch, this flexible supply exceeds the structural supply. In Rotterdam, it’s exactly half and in the rest of the cities the structural supply is bigger. A permanent supply makes students less vulnerable, as the monitor’s creators note.

International students

The housing shortage amongst students is also connected to the arrival of international students. Director De Bie warns that recruiting foreign talent will get more difficult if these students can’t find a room. ‘Our neighbouring countries can often guarantee this housing, which makes the Netherlands increasingly uncompetitive.’

Incidentally, some political parties think reducing the number of foreign students would be the solution. But critics believe this wouldn’t be good for the knowledge economy in the long run, given the labour market shortages.

Solutions

Other solutions? For one thing, Kences suggests more flexible rules for house sharing in municipalities. The nuisance argument should sometimes carry less weight than the housing crisis. Temporary contracts for students should also be made possible again.

The National Student Housing Monitor is conducted by ABF Research and commissioned by Kences and the Ministry of Housing.

The shortage of student rooms currently stands at 21,500. This is the difference between supply and demand when it comes to student housing. Students who’ve given up hope and stopped searching altogether are excluded from this figure. The same goes for secondary vocational education students.

If things continues like this, the room shortage could reach anywhere between 26 and 63 thousand by the 2032/2033 academic year. Although the number of Dutch students is decreasing and the number of foreign students is hardly rising anymore, private supply is declining even faster.