The genie is out of the bottle: how students and scientists are increasingly embracing AI

-

Illustratie: JeRoen Murré

Illustratie: JeRoen Murré

AI has become an integral part of campus life. Tools like ChatGPT are making everyday life easier for both students and academics, according to a survey by Vox. However, how far one is allowed to go with this remains a topic of debate. The university is working on tighter regulations.

When Steven Trooster returned to campus in early 2023 after the Christmas holidays, there was no easing into the new year. This was due to the recent launch of the public version of ChatGPT. ‘There was panic,’ the education advisor recalls. ‘It was clear this would have major implications for higher education.’

New Vox

This article is from the new edition of Vox, which is entirely dedicated to AI. In this magazine, you’ll find everything about the impact of artificial intelligence on education, research, and student life. Did you know, for example, that ChatGPT has some pretty interesting ideas for a student-style day in Nijmegen? But not everyone is a fan: three students share why they want nothing to do with AI tools. They’re doing their best — as much as possible — to keep AI out of their daily lives.

Not long after, stories began surfacing of students successfully using the free chatbot from OpenAI to write their papers. AI has been a hot topic at Dutch universities ever since, though much about the phenomenon remains unknown. Is artificial intelligence a fundamental threat to quality academic education and research, or a ‘promising’ revolutionary tool like the calculator once was? And how often do students and researchers actually use programs like ChatGPT or Midjourney?

Vox launched a survey to map out opinions on this at Radboud University. Over 350 students and 130 academics filled out questionnaires about their use of AI in education and research.

AI is well integrated on campus. Seventy percent of students use it one or more times a week. These figures align with a recent AI skills study by Radboud In’to Languages among over 300 first-year students in the Faculty of Science. Nearly two-thirds reported regular to frequent use of AI, while a quarter said they rarely or never use it.

The percentages also align with academics’ estimates. Most believe at least three-quarters of students use AI for their studies. Only 5% suspect that fewer than a quarter do. Half of the academics themselves use AI monthly or more often.

ChatGPT is by far the most popular tool. Six out of seven students and researchers have used this large language model (LLM) at some point. Other generative AI programs like Perplexity, Gemini, and Deepseek lag far behind, with usage rates of just 5–10%.

ChatGPT is by far the most popular tool. Six out of seven students and researchers have used this large language model (LLM) at some point. Other generative AI programs like Perplexity, Gemini, and Deepseek lag far behind, with usage rates of just 5–10%.

Googling

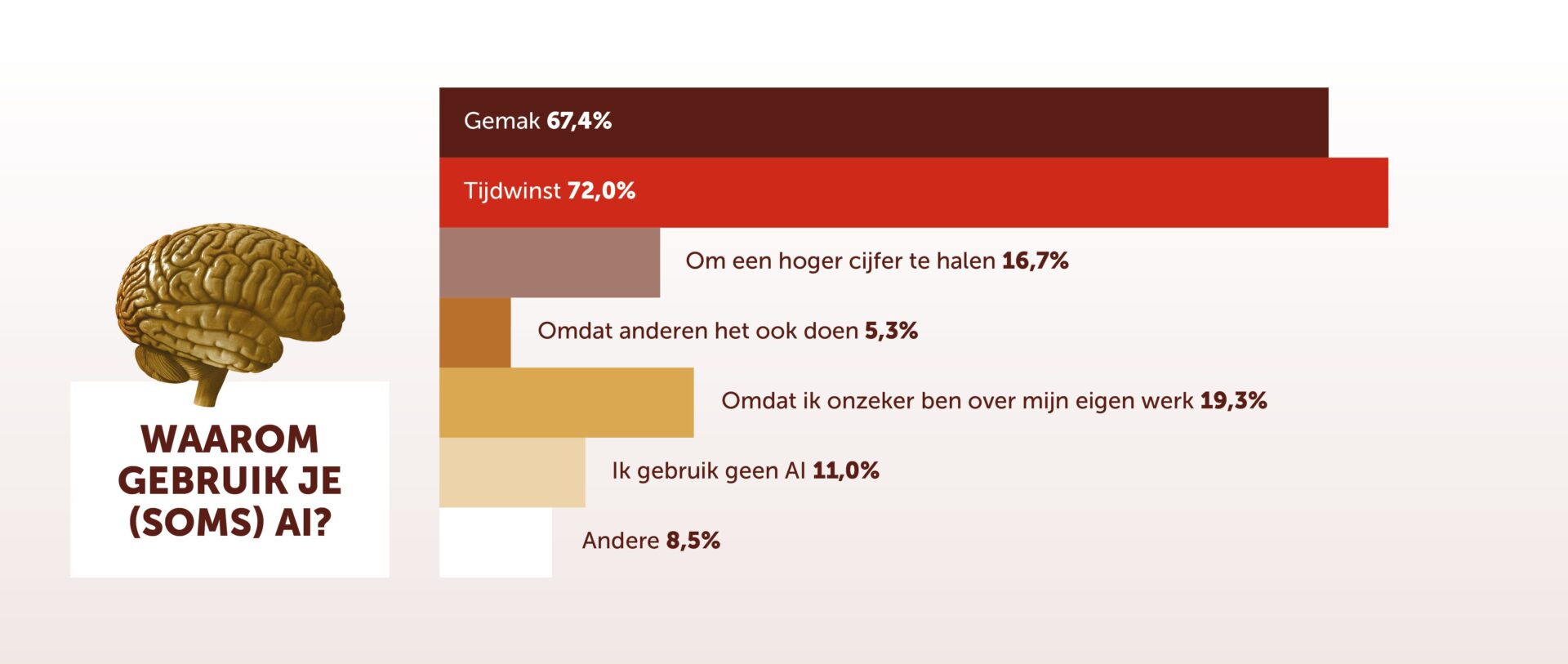

‘Time-saving,’ ‘convenience.’ Ask students why they use AI for their studies, and these answers stand out. Two-thirds mark these as reasons. ‘I just see it as Googling, but more efficient,’ one student explains. ‘Reading an AI-generated summary can help with understanding a text,’ says another. Only one in six students uses ChatGPT with the aim of achieving higher grades.

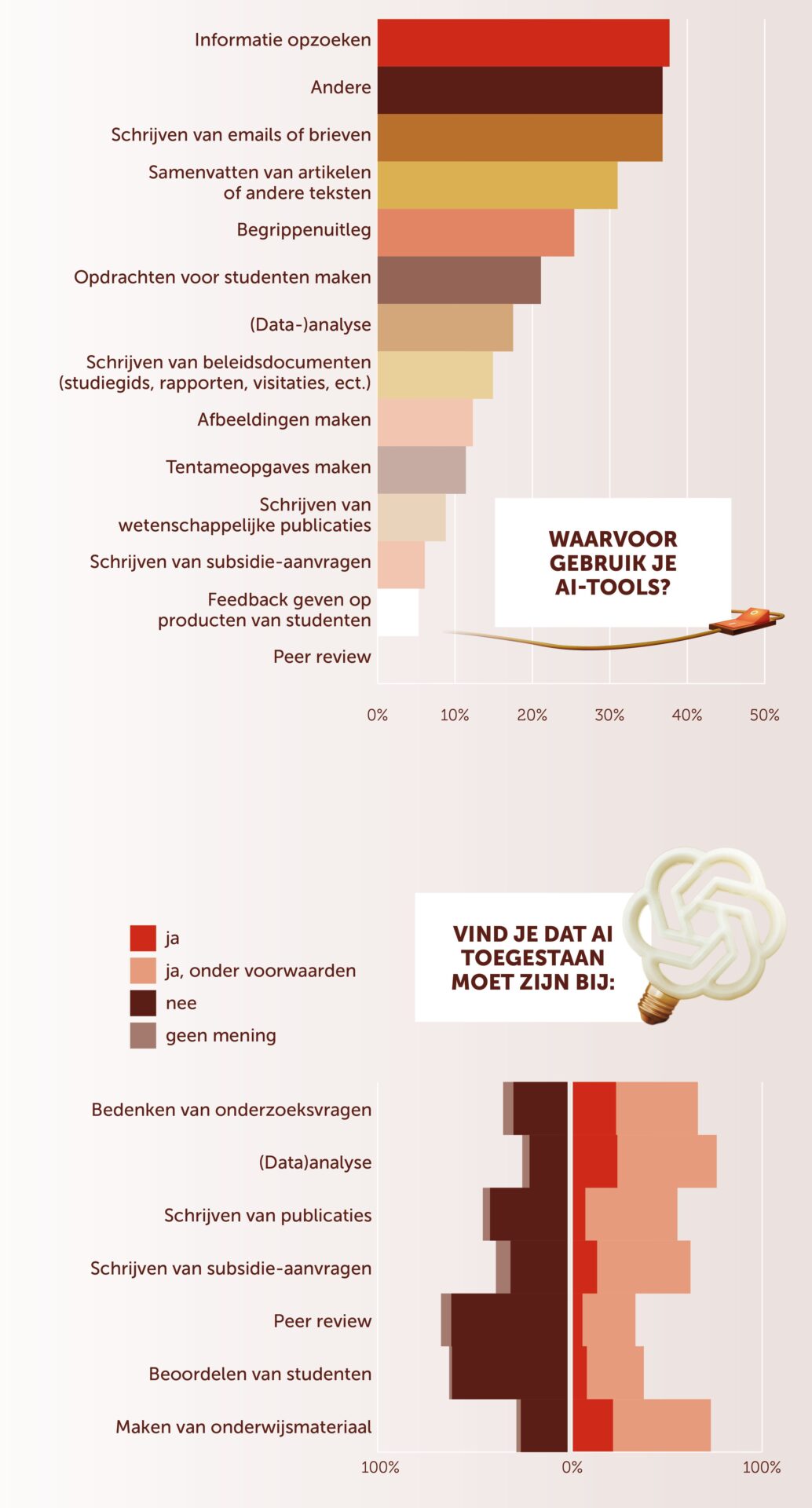

Academics use AI tools for similar purposes. A quarter to a third mention searching for information, explanations, summarising, and administrative tasks like writing letters, policy documents, or course catalogue entries. ChatGPT is described by one professor as a fully-fledged conversation partner ‘with an incredible amount of knowledge and insight’, though, like humans, it sometimes makes mistakes.

Nearly one in five academics has ChatGPT create assignments for students. They also use generative AI for spelling and grammar checks, translations, and writing code. ‘We have PhD candidates from all over the world, and they sometimes struggle with English when writing their dissertations,’ explains physics professor Nicolo de Groot, an enthusiastic AI user. ‘They use ChatGPT to improve their text.’ De Groot, former vice-dean of education, also uses AI to develop exams. ‘One of the questions in the most recent exam was: ask this question to ChatGPT and critically assess whether the answer is correct.’

Iris van Rooij, on the other hand, views the embrace of AI by students and staff with dismay. As a professor of AI, Van Rooij has always been publicly critical of what she calls the ‘hype’ surrounding tools pushed by big tech companies. ‘It’s worrying that universities are going along with this.’ She believes these tools shouldn’t be used at all: every prompt consumes large amounts of energy, LLMs are trained on copyrighted texts, and their underlying models are inaccessible and therefore unverifiable.

Iris van Rooij, on the other hand, views the embrace of AI by students and staff with dismay. As a professor of AI, Van Rooij has always been publicly critical of what she calls the ‘hype’ surrounding tools pushed by big tech companies. ‘It’s worrying that universities are going along with this.’ She believes these tools shouldn’t be used at all: every prompt consumes large amounts of energy, LLMs are trained on copyrighted texts, and their underlying models are inaccessible and therefore unverifiable.

But above all, she sees tools like ChatGPT as disastrous for academic development. ‘Your own brain is turned off. The purpose of a university is to learn to think independently and critically.’ Summarising, she stresses, is a prime example of an analytical skill developed during academic education. ‘You interpret information through your own cognitive lens, leading to different insights than someone else might have. That’s what science is all about.’ If you feed everything into ChatGPT, you end up with homogenised results.

Detection software

How are instructors dealing with student use of AI? Half believe students benefit from unauthorised use in their courses. Nearly three-quarters check for this in some way, such as by paying attention to writing style and source use. Only 5% use AI detection software.

Despite the benefits students mention, they generally don’t believe AI leads to much better, or worse, academic performance. Nearly all say they could manage without it, though a majority would miss the tools. One master’s student points out that ChatGPT makes education more accessible ‘for people who traditionally struggle with writing, like those with dyslexia.’

Notably, one in nine respondents say they never use AI. The most cited reason (by one-third of non-users) is the unreliability of ChatGPT’s output, though environmental and copyright concerns also play a role. Twenty percent of non-users consider AI use to be cheating, and 12% are mainly afraid of being caught.

Reliability is also a concern for students who do use ChatGPT. Five out of six regularly verify the answers they receive. A quarter say they always do so.

Clearer rules

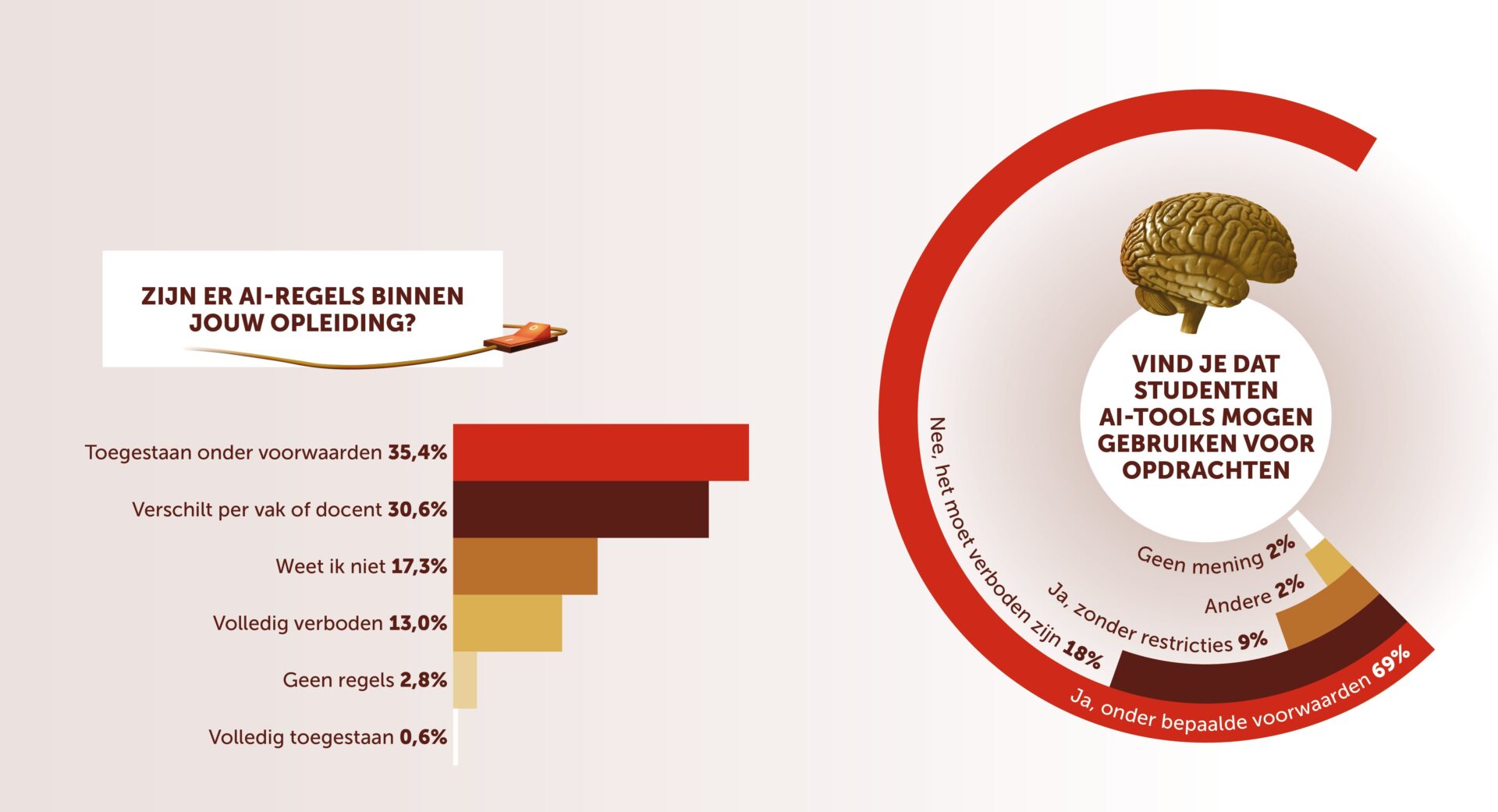

There is a strong desire for clear regulations, according to almost all students and staff. Most instructors believe these rules should be established at the university or faculty level. Students note that current AI policies vary widely. In one course, AI use might be completely banned; in another, it’s encouraged for experimentation. Instructors are more likely to say current guidelines are too lenient (41%) than too strict (15%).

‘Students need to know where they stand’

Surprisingly, one in six students says they have no idea what the AI rules are in their program. Among academics, over a third selected the same response. ‘The university should include AI in the OER (Education and Exam Regulations),’ one student argues. ‘Students need to know where they stand.’

When the rules are clear, students generally don’t break them en masse. Only 5% say they do so frequently, 15% occasionally. Just eight of the 353 students reported being caught for unauthorized AI use. Consequences included a lower grade, a failing mark, or referral to the exam board.

No matter how future regulations take shape, AI professor Iris van Rooij argues that outright banning AI is not the answer. ‘We already have academic integrity standards. These can apply here too. For instance, you can’t claim authorship of a text that someone else wrote or co-wrote. That includes ChatGPT, which is trained on the work of others.’

She finds it helps to explain the downsides of ChatGPT to students. ‘That’s also the responsibility of educators. I often hear: why were we never told this?’ She also has students sign a declaration promising to complete all assignments themselves.

Photocopiers

What about researchers? When may they use AI tools? A large majority believe AI tools are acceptable, with or without conditions, for data analysis, writing grant applications, and creating educational materials. ‘We embraced photocopiers, word processors, and the internet, didn’t we?’ one respondent asks rhetorically.

Across the board, researchers think AI positively impacts research quality (scoring 7 out of 10 on average). However, they distinguish clearly between types of AI. A language model like ChatGPT has very different applications than AI software that analyses X-rays or predicts 3D molecular structures like AlphaFold. For these ‘hardcore computational and recognition tasks, AI in the form of machine learning can be extremely useful,’ one respondent emphasises.

‘AI is changing the way we do things. It wouldn’t be right to keep that outside the university walls’

Researchers are much more skeptical about using AI for academic quality assessment, such as student evaluation or peer review. Only 7.5% find this unconditionally acceptable. ‘I’m […] against using generative AI to turn research results into articles or other written products,’ one researcher explains. ‘These are skills every researcher should possess.’

Still, AI has crept into the peer review process, Nature recently reported. The journal cited a French ecologist who received a review comment reading: ‘Here’s a revised version of your assessment with more clarity and better structure.’ According to a Wiley publisher survey, one in five researchers sometimes uses AI for peer review. Critics fear the emergence of an ‘echo chamber’ where AI handles both writing and evaluating scientific publications.

(Continue reading below the image)

Van Rooij, unsurprisingly, is strongly opposed to the use of commercial, opaque AI tools in academic research. For the same reasons mentioned earlier, but especially because she believes the use of tools like ChatGPT violates the scientific code of integrity. That code requires science to be verifiable and reproducible. ‘That simply isn’t possible if you use ChatGPT.’

Ideally, Europe should strengthen its own AI capabilities and develop more responsible tools, Nicolo de Groot agrees. At the same time, he acknowledges that ChatGPT’s momentum seems unstoppable. ‘AI is changing the way we do things. It wouldn’t be right to keep that outside the university walls.’

Denmark

Vox’s survey, despite its limited scale (see box), aligns well with other research. For instance, science sociologist Serge Horbach (FNWI) conducted a similar study last year on generative AI use among over 2,500 researchers in Denmark, where he was working at the time. The study was recently published in Technology in Society.

The Danish respondents, like those in the Vox survey, were strikingly positive about AI in general, Horbach explains. ‘They use it to conduct more and more complex analyses, improve text readability, and lighten administrative workloads.’

At the same time, nearly everyone was very cautious about using AI for the essential aspects of science. ‘Generating research ideas or peer review, for example. Incidentally, many academic publishers also forbid the latter,’ says Horbach.

Aware of the risks

That kind of clarity is currently missing at Radboud University, the survey results show. But behind the scenes, the university is indeed working on policies for generative AI use. As early as 2023, when there was still ‘panic in the tent,’ policy staff and academics drafted a university memo at the request of the executive board. It didn’t lead to detailed regulations, as each faculty was considered to face unique challenges. What is a dilemma in one place may be less so elsewhere.

European fines

To mitigate the risks of AI, the European Union’s AI Regulation has been in effect since August 2024. This law requires companies and organisations to map out the use of AI tools among their employees, along with the associated risks.

Organizations that fail to comply risk fines of up to 35 million euros. That is why Radboud University is conducting an AI survey among staff and students this spring.

At the same time, the university is working on its own online AI register. SURF, the ICT cooperative for education and research, is also developing a platform that provides users with an overview of various open-source AI tools.

Since then, various faculties—such as Arts, Social Sciences, Management, and Medicine—have developed their own AI guidelines. The message is largely the same: AI use is not forbidden, but be aware of the risks and use it critically.

A new steering committee is now developing university-wide rules, commissioned by the executive board. Policy officer Jorn Bunk shares expectations for the upcoming guidelines. Responsible use remains the core principle, extending beyond plagiarism and integrity. ‘Public values matter—like sustainability and independence from big tech. And of course, programs will have the space to define how AI should or shouldn’t be used. That may include situations where AI is entirely prohibited.’

The university is also developing an AI register to list the possibilities and risks of each tool (see box).

In the meantime, the university wants to more tightly control student and staff use of AI tools. It recommends using Microsoft365 CoPilot Chat instead of ChatGPT, as it offers better data protection. Whether people will actually follow this advice remains to be seen – almost none of the Vox respondents use this tool.

About this story

The two online surveys were open from February to April. A total of 353 students and 133 researchers completed them. 91 percent of the students were Dutch, and three-quarters were enrolled in a bachelor’s program. The Faculty of Social Sciences was overrepresented (41 percent), while law students were nearly absent (2 percent).

Among the researchers, PhD candidates and assistant professors (UDs) made up the largest group of respondents, followed by full professors, lecturers, and associate professors (UHDs). A quarter held another position.